1. Introduction

Overtone is an audio programming library useing the Supercollider syntheizer engine via the expressive programming language Clojure. It combines the power of Supercollider and Clojure enabeling many artistic endeavors, including:

-

Sound design

-

Musical composition

-

Midi/OSC hardware interfaces

-

Audio-visual compositions/installations

-

Data science and "big data" art

-

Live-coding

-

DAW integration

-

AbletonLive clock synchronization via AbletonLink

-

RaspberryPI/Bela/Monome compatability

1.1. Preface

It is my hope that this book will be a gentle introduction to Overtone for a complete beginner as well for a novice. I hope to approach the topic of Overtone with a grain of cynicism; "what can go wrong will go wrong". Overtone is still a highly unstable library and for a workshop of 6-8 participants, it takes usually half an hour or less to get everyone started. That said, you’ll most likely encounter redundant details and/or debugging instructions for highly improbable scenarios while reading this book. Keep in mind that what may seem obvious to you isn’t necessarily obvious to everyone.

The computer can be an amazing, exciting tool to fulfill our creative needs. But at the same time the computer, and its building blocks, computer programs and code, can be at times indescribably painful, misconfigured and unpredictive. The hurdles you may encounter may include tooling, mac/linux/windows specific problems, files and libraries mislocated, version incompatibilities, and the list can go on forever. Luckily we will be getting ourselves comfortable with the programming language Clojure, which in the total 10 years of its existence, has seen an explosion of book publications, tutorials, workshops and stackoverflow questions/answers. So if you find youself in the unfortunate situation of getting stuck with something unrelated to Overtone, your odds are good that someone else on the internet already had the same problem as you, and you’re only one google search away from getting yourself back on track. At any point in time for any problem you are facing, you should always feel welcome to open ticket on github, ask question on stackoverflow, the irc(freenode) or on slack(clojurians). The software community as a whole is riddled with micro-aggressive "bromance" behaviour and hence can be at times quite intimidating for beginners to reach out for help. Which among other factors(in my subjective opinion), we end up with demographics of coders, be it art related or not, completly out of proportion in relation to the demographics of the general population. Please be aware that the Clojure community has on all social-media platforms, meetups and conferences a set of guidelines for behaviour, protocols in case of violation and group of confidentials to report violations to. I believe that these measures has made the Clojure community relatively more inclusive and diverse, every day I see experienced developers go out of their way to help someone in need of help and I hope you will enjoy the benefits of the Clojure community in the same way as I did when I was a total beginner.

As my personal advice as an artist to artists stepping into the journey of creative coding: don’t believe everything software engineers tell you about software, in the same way you shouldn’t believe everything an artist tells you about how art should be. An artist and software-engineer will and should approach code in different ways. You will never hear stories about Beethoven implementing a Continous Integration test to determine if his 7th symphony accidentally lost a note while he was writing his 8th, or Stravinsky trip out on his Bassoon type checker when he wrote the introduction to the Rite of Spring. Learning from the best is always a good approach and becoming better at programming is only going to make you faster and more effective, but do watch out for the abyss of infinite information and take moderate actions. If our goal is to create art for the real world, be completely shameless if your code isn’t orthodox as long as it produces the desired result and you had fun writing it. While the "old-school" composer is sitting next to a piano with pen and empty staff notation paper, in the same way you will find ourself with an empty text document in your text editor, with your fingers on the keyboard, ready to explore the physical boundaries of music, sound and time.

1.2. About this Book

1.2.1. Work in Progress

This is a work in progress. If you find an error, please submit a PR to fix it, or an issue with details of the problem.

1.2.2. Contributing

This source for this book is hosted on Github.

1.2.3. Conventions Used

The examples and code used in this book will try to be as neutral as possible when it comes to choice of text-editor. All modern text editors have some sort of plugin to run and evaluate Clojure code. If you are starting out with the programming language Clojure, you may easily get confused or lost on how to replicate some of the examples in your text editor. Therefore we aim to make all of our examples replicable using nothing but Leiningen in the terminal via lein repl, and assume from the reader basic understanding of the terminal/cmd (if you know how to explore directories and install apps with the terminal, you probably know enough). Leiningen is the most popular build tool in Clojure and is the build tool that glues Overtone’s sources and dependencies together. Overtone does work with alternative build tools like boot, as well as a standalone java jar file, but that and how to integrate Overtone to specific text-editor will not be included in this book.

Please be also aware that topics often overlap. If something isn’t clear, have a look at the chapter titles to see if the concepts you’re trying to understand is explained elswhere in the book.

2. Installation

2.1. Dependencies

You will need:

Optionally you could want:

-

Supercollider for starting scsynth externally from Overtone

-

Git for cloning the Overtone repository from github

If running on Linux you must have JACK Audio connection toolkit version 2 or later (which qjackctl provides along with easy to use GUI)

$ sudo apt-get install qjackctl$ sudo dnf install qjackctl$ sudo yum install qjackctl$ nix-env -i libjack22.2. Setting up a project

Although it is possible to start Overtone directly from the github repository by downloading it as zip or cloning it with git clone https://github.com/overtone/overtone.git in the terminal, it is recommended that Overtone is used as any other Clojure library in your own project. So we will do exacly that.

First create an empty directory, we’ll call it overtone (the name is irrelevant here) and go into it

$ mkdir overtone

$ cd overtoneThen in your text-editor, create a new textfile and save it into the newly created directory as project.clj. This is file that leiningen looks for inside the folder leiningen was started from (ie. you can’t start leiningen in directory x and expect it to find project.clj in directory y). Then paste the following code into project.clj and save the file again.

(defproject overtone-tutorial "1.0.0"

:dependencies [[overtone/overtone "0.10.3"]]

:native-path "native"

:source-paths ["src"])With only one file in your directory run the following lein command and let’s see what happens

$ lein deps

lein deps is actually a redundant command as lein repl implicitly fetches Clojure dependencies before starting the REPL. It is only useful if you want to fetch the dependencies without starting the REPL.

|

If you’re running leiningen for the first time you should see a whole bunch of text appearing on the screen, indicating that leiningen is downloading the Clojure dependencies needed to run Overtone. After this process, directories target and native should have been created, both of these directories can be safely omitted if you’re planning on saving your code on for example github, and target can even be deleted at any time, by literally deleteing it or by running lein clean which by default deletes target, that will only be useful if you’re trying to debug your program as target gets created every time you run leiningen to store various information irrelevant to us at this moment. But do keep native untouched as it stores the necessary files needed to run Supercollider from within Overtone.

Now let’s start Clojure via lein repl

$ lein repl| REPL stands for READ-EVAL-PRINT-LOOP, and is a fancy word for the Clojure shell/interpreter. In simple terms, a [Clojure]REPL is any type of program or tool that you can give Clojure code to to be evaluated. |

If all went right, you should see something similar in your terminal window

nREPL server started on port 34189 on host 127.0.0.1 - nrepl://127.0.0.1:34189

REPL-y 0.3.7, nREPL 0.2.12

Clojure 1.9.0

OpenJDK 64-Bit Server VM 1.8.0_172-02

Docs: (doc function-name-here)

(find-doc "part-of-name-here")

Source: (source function-name-here)

Javadoc: (javadoc java-object-or-class-here)

Exit: Control+D or (exit) or (quit)

Results: Stored in vars *1, *2, *3, an exception in *e

user=>Now for our sanity, let’s see if this REPL prints Hello World

user=> (println "Hello World!")

Hello World!

nil

user=>Yup we are ready, then to the moment of truth, now let’s boot up Overtone with this easy-to-remember command

(use 'overtone.live)If all went accordingly without errors you should see something similar in your terminal window, note that I’m running here on Linux, so for me Jack will be automatically booted and connected.

user=> (use 'overtone.live)

--> Loading Overtone...

--> Booting internal SuperCollider server...

Found 0 LADSPA plugins

Cannot connect to server socket err = No such file or directory

Cannot connect to server request channel

Cannot lock down 82280346 byte memory area (Cannot allocate memory)

Cannot use real-time scheduling (RR/5)(1: Operation not permitted)

JackClient::AcquireSelfRealTime error

JackDriver: client name is 'SuperCollider'

SC_AudioDriver: sample rate = 48000.000000, driver's block size = 2048

--> Connecting to internal SuperCollider server...

--> Connection established

JackDriver: max output latency 128.0 ms

_____ __

/ __ /_ _____ _____/ /_____ ____ ___

/ / / / | / / _ \/ ___/ __/ __ \/ __ \/ _ \

/ /_/ /| |/ / __/ / / /_/ /_/ / / / / __/

\____/ |___/\___/_/ \__/\____/_/ /_/\___/

Collaborative Programmable Music. v0.11

Hello Hlolli, may algorithmic beauty pour forth from your fingertips today.

nil

user=>If something went wrong, see if the stacktrace gave you any meaningful information and proceed to Configuration and try to rule out that something isn’t misconfigured. And come back here and try to start Overtone again before continuing. A good rule of thumb is to read stacktraces from top to bottom, the uppermost lines being the most important ones in most of the cases.

If you’re on Linux too and encounter Cannot allocate memory and/or Cannot use real-time scheduleing you can totally ignore that, it just means that you’re not running preempt realtime-kernel. Switching to rt-kernel can potentially improve your audio performance by allowing Jack to send audio on top priority, but at the cost potentially make things very complicated and possibly insecure, as rt-kernels are usually released that much later than other kernels. If you want to run proprietary nvidia/ati drivers on preemt rt-kernel, you’re most likely going too have a bad time, irrelevant if you’re a linux expert or a beginner.

|

Now that we have Overtone running successfully. We can start all the functions that Overtone provides at our disposal. Among them is an important helper function called doc, which will print the documentation to any function in your scope/reach. Let’s try it on the symbols demo and sin-osc.

user=> (doc demo)

-------------------------

overtone.live/demo

([& body])

Macro

Listen to an anonymous synth definition for a fixed period of time.

Useful for experimentation. If the root node is not an out ugen, then

it will add one automatically. You can specify a timeout in seconds

as the first argument otherwise it defaults to *demo-time* ms. See

#'run for a version of demo that does not add an out ugen.

(demo (sin-osc 440)) ;=> plays a sine wave for *demo-time* ms

(demo 0.5 (sin-osc 440)) ;=> plays a sine wave for half a second

nil

user=>user=> (doc sin-osc)

-------------------------

overtone.live/sin-osc

([freq phase mul add])

Sine table lookup oscillator

[freq 440.0, phase 0.0, mul 1, add 0]

freq - Frequency in Hertz

phase - Phase offset or modulator in radians

mul - Output will be multiplied by this value.

add - This value will be added to the output.

Outputs a sine wave with values oscillating between -1 and

1 similar to osc except that the table has already been

fixed as a sine table of 8192 entries.

Sine waves are often used for creating sub-basses or are

mixed with other waveforms to add extra body or bottom end

to a sound. They contain no harmonics and consist entirely

of the fundamental frequency. This means that they're not

suitable for subtractive synthesis i.e. passing through

filters such as a hpf or lpf. However, they are useful for

additive synthesis i.e. adding multiple sine waves

together at different frequencies, amplitudes and phase to

create new timbres.

Categories: Generators -> Deterministic

Rates: [ :ar, :kr ]

Default rate: :ar

nil

user=>Much of what is written in the documentation will be explained in subsequent chapters. But let’s suffice to say that demo is a function intended to evaluate an instrument and play it immediately for 2 seconds, which can come in handy when developing sounds and you want to hear the results quickly. And sin-osc is an oscillator that produces sinewave shape audio-signal (or control-signal, more on that later). Unlike demo which needs at least 1 instrument to be given as a parameter, then sin-osc can be called without any parameter, if that’s the case, then sin-osc will look at its own default parameter and use those instead. Which would be 440 cycles per second on full amplitude.

We will conclude this chapter by playing 2 seconds of 440Hz sinewave. It won’t sound pretty but it’s a fast and effective way to determine if everything is working accordingly.

(demo (sin-osc))If you’re at this point not hearing any audio, and you’re sure that nothing is muted on your computer. Then have a look through the Configuration chapter before opening a ticket.

3. Basics

3.1. Envelopes

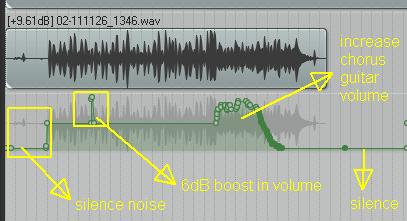

Application of envelope via graphical breakpoints

The term envelope may or may not sound alien to you. But if you’ve ever used attack or decay on modular synthesizer or written breakpoints in a DAW like Ardour, ProTools or Reaper, you have used envelopes. Fade-in and fade-out are other commonly used forms of an envelope. The basic idea is that as time passes, often shown as x-axis in a plot, some value changes accordingly, often drawn on y-axis. In fact an envelope can be an oscillator and an oscillator can be used as an envelope.

Envelopes are most traditionally used to control amplitude and frequency, as will be shown later, envelopes in Overtone can be used for many other things, like amplitude modulation, oscillation, trigger, arpeggiator, trill/tremolo ornaments. Basically anything that ties numbers and time together.

3.1.1. Shapes

Overtone has a function to create envelope shapes in a format that Supercollider understands, called simply envelope. For every envelope there needs to be two vectors provided as arguments, levels (y-axis) and durations in seconds (x-axis), since durations specifies the durations of each step, its size will need to be the size of the levels vector minus 1. You can choose an envelope shape by directly specifying each point via :step, or use one of the following keywords to apply a function to your points.

-

:lina linear function that creates straight lines from given points -

:expa natural exponential function (eⁿ), no value on y-axis can be zero -

:sinapplies Hann function to given points -

:wela power spectrum generator via Welch method -

:sqrapplies square (n²) function to given points -

:cubapplies cubed (n³) function to given points

Let’s try a simple example.

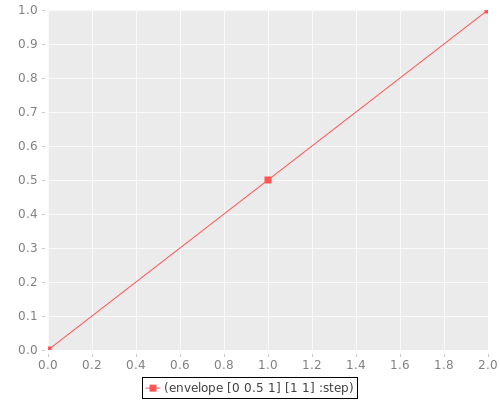

(envelope [0 0.5 1] [1 1] :step)This shape will create a straight line from 0 to 0.5 and from 0.5 to 1, with each of the two steps taking 1 second (totalling 2 seconds, which is the default time demo plays an instrument).

To most clearly hear what’s going on here, let’s try to play this line as an upwards glissando(gliding note) from 200Hz to 400Hz and see if this works.

(let [env (envelope [0 0.5 1] [1 1] :step)]

(demo (sin-osc :freq (+ 200 (* 200 (env-gen env :action FREE))))))This clearly didn’t sound like glissando, so what’s going on here? We did indeed specify a line from 0 to 1 and multiplied the line by 200 to glide 200Hz ending at 400Hz. By useing :step the envelope makes no attempt bridge the gap between the points we provided it. So as soon as the instrument started we heard 300Hz and halfway through it changed to 400Hz. So what happened to our first point of 200Hz? In those cases where the envelope loops, there’s a chance of distorted hum if the envelope doesn’t begin where it ends, so point 0 on x-axis works as a pivot point and will never be played.

Let’s try again, but this time let’s try to bridge the gap by applying a linear function to the points using :lin.

(let [env (envelope [0 0.5 1] [1 1] :lin)]

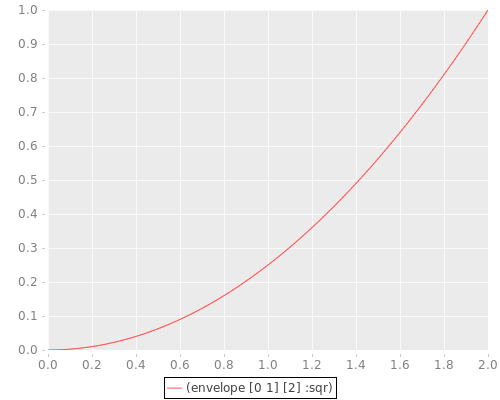

(demo (sin-osc :freq (+ 200 (* 200 (env-gen env :action FREE))))))This sounded much smoother, no jumps but a constantly gliding note for the duration of the two seconds. But to human ears, this linear glide doesn’t sound very linear even though the computer did perfectly good job of executing it linearly. To produce a glissando that a human would sing or perform on a violin, we need to apply a non-linear function to the provided points. Keep in mind our auditory senses are non-linear both for the perception of amplitude and frequency. Where we usually control and measure amplitude on logarithmic scale in decibels, and frequency with note names, midi note number or pitch class sets, all of which are in in squared relationship to the Hz they represent. So for our last attempt glissando, we’ll apply a squared function to points from 0 to 1 in 2 second interval.

(let [env (envelope [0 1] [2] :sqr)]

(demo (sin-osc :freq (+ 200 (* 200 (env-gen env :action FREE))))))

The envelope function can also take a number and/or vector of numbers instead of keywords for the shape. In that case, 0 marks a linear curve and the higher the number, the curvier. Negative values means curve in the opposite direction. These can produce interesting curves which can be hard to visualize, you may want to try the examples from the Supercollider documentation in your Supercollider and use the nice plotter as aid. Env.new and envelope do the same thing.

|

3.1.2. Built-in envelope shapes

Like mentioned, you can use the function envelope to define any arbitrary shape you want via :step and apply various function to a vector of provided points. But most of the time you’ll want to use built-in functions that provide the most commonly used envelope shapes for sound-designing.

-

adsrcreate an attack decay sustain release envelope -

lincreates a linear trapezoidal shaped envelope -

perccreates non-linear exponentially shaped envelope -

trianglecreates an envelope which has triangle shape -

sinecreates a hanning window shaped envelope -

asrcreates attack sustain release envelope

Additionally you’ll find in Overtone: adsr-ng, step-shape, linear-shape, exponential-shape, sine-shape, welch-shape, curve-shape, squared-shape and cubed-shape.

3.1.3. env-gen and linen

All shapes returned by envelope, or the built-in envelope functions which themselves are all built on top of envelope, must be used in combination with env-gen. env-gen is what turns the envelope data into a signal which can be passed around as an operator to other signals, as well as direct argument to various inputs. The first parameter of env-gen is the aforementioned envelope shape itself. The other parameters are as follows gate, level-scale, level-bias, time-scale and action.

A lesser used minimal alternative ugen to env-gen is linen. linen is a linear attack-sustain-release envelope generator that takes only gate and action as extra arguments and runs only on control-rate (see Data Types to understand the various rates) and returns a signal that can be used in the same manner as env-gen.

The following two expressions will be played exactly the same.

(demo (* (env-gen (lin 0.1 1 1 0.25) :action FREE) (sin-osc)))

(demo (* 0.25 (linen (impulse 0) 0.1 1 1.9 :action FREE) (sin-osc)))3.1.4. Other ways to envelope

Since an envelope can be any modulating signal, we can create an envelope shape using low-frequency-oscillators or LFO for short. A low-frequency-oscillator is typically an oscillator that oscillates at a frequency under the lower limit of human hearing range ~22Hz. In overtone you can find LFO oscillators starting with LF, which include lf-saw, lf-par, lf-pulse, lf-tri and countless more. They differ only from traditional oscillators in that they are not band-limited and are more performant, since they don’t try to anti-aliase high frequencies. When working with LFO’s in most cases, it doesn’t matter if you use band-limited or non-band-limited oscillators, they behave exactly the same on low frequencies.

The following expression plays a sawtooth oscillator for 1 second with even attack and decay time created from the shape of sinewave. Note that we are converting Hertz(1/sec) to seconds, as reference 1Hz takes 1 second to finish 1 cycle. As we are using sinewave shape from sin-osc:kr we are only concerned with the positive values from 0 to 1, which occupy the first half of the sinewave. Therefore we multiply the wanted note duration by 2, so that the signal cuts off exacly before the sinewave goes from 0 to a negative value. The line:kr serves as timeout that frees the synth node after 1 second and hence prevents it from playing the full 4 seconds which the demo time defaults to.

(demo (let [dur 1

env (sin-osc:kr (/ 1 (* 2 dur)))]

(line:kr 0 1 dur :action FREE)

(* env (saw 220))))Now if we wanted a sinewave envelope with two peaks, we need to apply abs (asbolute value) on the LFO signal so as not to end up with negative amplitude values. Here we don’t need to cut the sinewave signal in half since applying abs causes the sinewave to become unipolar (from 0 to 1) as opposed to bipolar (from -1 to 1).

(demo (let [dur 1

env (abs (sin-osc:kr (/ 1 dur)))]

(line:kr 0 1 dur :action FREE)

(* env (saw 220))))We can also shift the sin-osc to become unipolar by using the parameter :add. By adding 1 to a bipolar signal, it will cause a shift from ←1,1> to <0,2>, and since we want to limit our range to be within the sensible amplitude boundaries of <0,1> we need to multiply the signal by 1/2 (or divide it by 2). That can also be achieved by setting the parameter :mul to 0.5 as shown below.

(demo (let [dur 1

env (abs (sin-osc:kr :freq (/ 1 dur) :mul 0.5 :add 1))]

(line:kr 0 1 dur :action FREE)

(* env (saw 220))))With a sawtooth oscillator we can emulate a linear fadein. Here we also need to convert the bipolar sawtooth-wave signal into unipolar signal.

(demo (let [dur 1

env (abs (lf-saw :freq (/ 1 dur) :mul 0.5 :add 1))]

(line:kr 0 1 dur :action FREE)

(* env (saw 220))))By providing negative :iphase value we can reverse the signal and get a linear fadeout.

(demo (let [dur 1

env (lf-saw :freq (/ 1 dur) :iphase -2 :mul 0.5 :add 1)]

(line:kr 0 1 dur :action FREE)

(* 0.1 env (saw 220))))3.1.5. Extra

Here are some tutorial videos about envelopes, not related specifically to Overtone, but can give ideas.

3.2. Oscillators

This section will cover oscillators in Overtone and more specifically wavetable oscillators; How we can create wavetable oscillators, how we can mix them and how we can use envelope to give a dull sound more liveness. First we will look at wavetables in depth educational purposes and then ever more practical application of wavetable synthesis in Overtone.

3.2.1. Wavetable

Wavetable synthesis with computers, explained at its essence, is the way of creating signal by reading phase values from a table and sending those values in sample-rate to a given audio source (also refered to as Liner Pulse-Code Modulation). In Overtone the phase values are stored between -1 and 1. As opposed to a 16-bit .wav file which stores its values as integers from 0 to 65,535 or −32,768 to 32,767 depending if it’s unsigned or signed integers respectively. Same goes for the audio hardware in your computer, if it’s set to 16-bits resolution, then supercollider will remap the floats between -1 and 1 to an integer range that the audio hardware expects to receive. When refering to phase in this context, can be misleading to newcomers. For oversimplification you can think of phase stored from samples and audio files purely as amplitude, since a signal going from -1 to 1 is playing audio on full amplitude strength. Whereas you may play your Overtone instruments with amplitudes that are in the range of 0 and 1 (there’s no such thing as negative amplitude), supercollider enginge will create a signal that has phase values from -1 to 1 and the audio module will take the signal from Supercollider and remap it to −32,768 to 32,767 (for 16-bit).

As a possible source of terminology misunderstanding. The concept of "table" here refers to an indexed iterateable list of values. Clojure has no concept of "table", so when discussing tables in Clojure land, we would be a refering to a vector (or other sequenable list). If refering to a table in Supercollider land, we would be refering to a Buffer.

|

That trivial knowledge above is quite irrelevant to our task of makeing wavetables in Overtone, but the connection of phase, amplitude, table and storage of audio is important to understand before we proceed. But let’s create a sinewave table with the following formula \$sum_(n=0)^L=sin(frac{2pin}{L})**A\$. Where L stands for table length (typically a number which is \$2^x\$) and A stands for the amplitude.

(let [L (Math/pow 2 10)

A 1]

(mapv (fn [n] (Math/sin (/ (* 2 Math/PI n) L))) (range 0 L)))

;; => [0.0 0.006135884649154475 0.012271538285719925 0.01840672990580482 0.024541228522912288....]With amplitude set to 1, we get a vector representing sinewave which goes from -1 to 1. Let’s turn this into a function that we can user later, where the amplitude is omitted (and hence returns values between -1 and 1). Also let’s return a buffer instead of a vector so we can play our result later on.

(defn generate-sinewave-buffer [len]

(let [wavetable-vector (mapv (fn [n] (Math/sin (/ (* 2 Math/PI n) len))) (range 0 len))

empty-buffer (buffer len)

wavetable-buffer (buffer-write! empty-buffer wavetable-vector)]

wavetable-buffer))Next thing to look out for is the relationship between the sample-rate and table-size. If you imagine the values in the table, which are 1024 being read one by one on the rate of 1/48000 per second (or \$frac{1}{sr}\$). Before 1 second has passed, our table would have been read almost 48 times, creating 48Hz audio signal instead of 1Hz. To compensate for that, we need a simple math to help us even out the relationship between the sample-rate and the table-size by dividing the table-size with the sample-rate. By doing that we can create our first wavetable-oscillator where we can have full control over the frequency of our signal.

(def our-sinewave-table (generate-sinewave-buffer 1024))

(demo (let [buf our-sinewave-table

frequency 440

table-size (buffer-size buf)

current-sample-rate (sample-rate)

playback-rate (* frequency (/ table-size current-sample-rate))]

(play-buf:ar 1 buf :rate playback-rate :loop true :action FREE)))Bravissimo Houston! By multiplying the wanted frequency to the ratio between table-size and sample-rate as defined in playback-rate above, we can modify the frequency as we wish. Later in the manual we will discuss samples, where the function play-buf:ar plays a huge role. With the difference that in wavetable synthesis we generate table representing one cycle, therefore we need to loop over the values multiple times a second to create an audible signal, whereas a sample is usually only played once trough.

Now we have to power to generate a vector in Clojure, send it to supercollider-land as a buffer and play back the values stored in the buffer with play-buf:ar. Now let’s proceed.